- Home

- Leonard Maltin

The Art of the Cinematographer Page 2

The Art of the Cinematographer Read online

Page 2

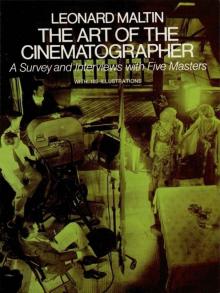

D. W. Griffith looks pleased with the scene he is directing for THE LOVE FLOWER (1920). Billy Bitzer is at the camera, Bert Sutch is one of the observers.

Harry Potamkin wrote, in a highly sophisticated analysis of motion picture photography in a 1930 issue of the Theatre Guild magazine: “The first use of the close-up [sic] in the movement of a narrative film was made in THE MENDER OF NETS, in which Mary Pickford acted and which Griffith directed and Bitzer photographed. . . . We may note here that in America the close-up has remained a device for effect. In Europe it has evolved as a structural element and has attained, in THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC, the eminence of a structural principle.

“It was he [Bitzer] who originated the soft focus. . . . In America, again, we have not gone on with these modifications of the literal in film photography. It is in Europe we find their continuation and extension. Cavalcanti films THE PETITE LILY through gauze to depersonalize the characters, and Man Ray sees his character through a mica sheet which grains the picture and renders it liquid constituency.

“The mind of the American film, regarding both content and approach, is literal; and that is why the American film is still rudimentary, and why no one here has extended or even equalled the compositions of Griffith or logically developed the innovations of Bitzer.” This is one man’s opinion, of course, but it does show the overwhelming respect and admiration which Griffith and Bitzer earned right from the start.

But these two men were alone in their filmmaking goals. While they exercised artistry in communicating ideas and sought visual beauty in their finished product, the rest of the American film industry was taking a different turn. The general trend was toward entertainment for the masses, an equally honorable aspiration for any director or producer, but one which brought with it a different set of rules. Art for art’s sake was jettisoned. Good photography, even creative photography, was encouraged—as long as it was an integral part of the picture and not a self-indulgent exercise in aesthetics.

Lest anyone think that this made cinematography less of a challenge, it should be explained that filmmaking was still in its infancy at this time. Natural light was still the prime source of illumination; cameras were still cranked by hand; the orthochromatic film the cameramen used was far from perfect, being insensitive to blue. These obstacles were only a few of the many critical problems cameramen faced just to get a decent picture on the screen. And the only answer was trial and error; there were no precedents to follow, no books to consult, no experts to ask. The great cameramen who emerged during this period (including those who are interviewed in this book) spent every spare moment experimenting on their own, trying to learn the many secrets of motion picture photography. Once assigned to shoot a picture, they were on their own, and had to know what they were doing.

In the early days, the cameraman also worked in the laboratory, developing his own film. While extremely hard work, doubling behind the camera by day and in the darkroom by night, it was invaluable training. It taught these men about exposures and filters; what they could and could not do with the camera, and how to utilize light to the best advantage. It also showed them what could and could not be corrected in the developing stage.

On top of other duties (and it must be remembered that cameramen generally did not have assistants at this time—they were the one-man cinematography department), many cameramen were responsible for taking still pictures of every film for advertising and publicity purposes. Still photography was the pathway to motion picture photography for many men, including James Wong Howe, who got into the film business in 1917. The story of how he became a cameraman is indicative of the challenges a cinematographer faced at that time, and a vivid description of the casual nature of Hollywood moviemaking.

“I was one of four assistants with Cecil B. DeMille,” Howe recently told a television interviewer. “I was with him for about three years, then I became what we called a second cameraman. We didn’t have operators in those days. The second cameraman would set his camera as close as he could to duplicate the shot of the first cameraman, and that negative was used to send over to Europe. It was called a foreign negative. Now we can duplicate and send a dupe over. So you graduated from assistant, to second, and from second you went to being chief photographer, and in 1922 I made my first picture.

Director F- . W. Murnan (right). Karl Struss (standing), and Charles Rosher (seated) make a shot of George O’Brien for SUNRISE (1927). ).

It was called DRUMS OF FATE, with Mary Miles Minter. I had photographed a portrait of Miss Minter with my little camera, and she liked it. I enlarged it and gave it to her. She said, ‘Oh, I look lovely in this picture; could you make me look like this in the movies?’ I said, ‘Why, yes.’ So two or three months later, I’m called in, and they congratulate me, to go down and get my camera—I’m now Mary Miles Minter’s cameraman. And she was one of the big stars. They said, ‘She wants to talk to you, Jimmy.’ I went down, knocked on the door of her dressing room, and she had the picture lying on her dressing table. She said, ‘You know why I like these pictures, Jimmy? Because you made my eyes go dark.’ She had pale blue eyes, and in those days the film was insensitive to blue, and they washed out. And I didn’t realize how I’d made her eyes go dark! I walked, and stood where I took the pictures, and there was a huge piece of black velvet. Something told me, ‘Well, it must be a reflection. The eye is like a mirror. If something is dark, it will reflect darker.’ So I had a frame made, cut a hole in it and put my lens through, and made all her close-ups that way. It helped her, because it blocked out all the accessories, and the people watching her, and she liked it because it made her eyes go dark. That’s how I became a cameraman. After a couple of pictures, Hollywood in those days, each star had his own crowd, they’d have parties, and the news spread around that Miss Minter had imported herself an Oriental cameraman, and he makes her eyes go dark by hiding behind a piece of black velvet. Everybody who had light blue eyes wanted to have me as their cameraman!”

This was the age of the star system, of course, and many stars jealously clung to certain cameramen who made them look good, and knew their business. Charles Rosher, a London-born photographer who moved to America in 1909 and made a name for himself by photographing the famous Pancho Villa newsreels, as well as many Hollywood films, was soon hired by Mary Pickford, literally the number-one star in Hollywood. Rosher remained with her for twelve years, and Pickford’s films were widely acknowledged as being the best photographed films in Hollywood. Rosher’s knowledge of lighting, along with his experience in still photography and his impeccable taste, made his reputation justified. Undoubtedly his masterwork was SUNRISE (1927), one of the great classic films, directed by F. W. Murnau, and co-photographed by Karl Struss. A moody, sensitively played film with a particular emphasis on the visual, SUNRISE is a German-oriented film (it was Murnau’s first in America), but with a lighter touch than most authentic German products. Its elaborate mounting cannot be exaggerated; the very thought that it was done largely on Fox’s back lot is staggering. But Rosher was an artist, as was Struss, and together with Murnau they created one of the most hauntingly beautiful films of all time.

Other cameramen were identified with certain stars, and in some cases, with directors, but some of the best cameramen never received recognition and remain ignored to this day. The reason is simple: they believed in functional photography, camerawork that was so good it would go unnoticed. Two of these unsung heroes were Rolland “Rollie” Totheroh, Charlie Chaplin’s cameraman, and Elgin Lessley, Buster Keaton’s cameraman.

Comedy is an exacting art, no matter what aspect one cares to examine. But in silent-screen comedy, photography was one of the most important factors: it had to be razor-sharp for the audience to catch everything that was happening; framing had to be precise, since the action was liable to depend on something occurring at the extreme top or bottom; the cameraman had to be versatile and inventive in order to capture many crazy stunts on film. The photography had to be

perfect in order for the comedies to be funny; sight gags are only good if they look real. Both Totheroh and Lessley had the skill and dedication to accomplish what was required for the comedies they filmed, and their exceptional work should not be forgotten.

Rolland Totheroh was a staff cameraman for Essanay Studios when Chaplin arrived there in 1915. Chaplin was directing his own films by this time, and he liked working with Totheroh; the feeling was mutual, and Totheroh remained Chaplin’s cameraman through MONSIEUR VERDOUX, in 1947. In many ways, Chaplin’s best films are the dozen two-reel comedies he made for the Mutual company in 1916 and 1917; they include such classics as EASY STREET, THE PAWNSHOP, and THE CURE. Appropriately, the photography of these films is also in many ways superior to that of the later, more elaborate, productions. Chaplin’s biographer, Theodore Huff, wrote, “The photography in the Mutuals has remarkable clarity, especially in good prints.” Totheroh knew that the secret of good photography in a comedy is to show the action on screen to the best possible advantage. Directorially, he and Chaplin knew exactly what setup would be right for each scene. Looking at a film like EASY STREET, it is impossible to find a shot that doesn’t do its job in the best possible way; there are close-ups, medium-shots, and long-shots; the camera dollies forward and backward to show Chaplin, a policeman, patrolling his block; it intercuts a long-shot with a medium-shot in order to catch one of Chaplin’s subtle moves when the villain is preparing to beat him up. Totheroh made a valuable contribution to Chaplin’s best comedies, and Chaplin knew it; few of his professional associations were as durable as that with Totheroh.

Buster Keaton’s brilliant comedies of the 1920s depended on elaborate sight gags, and Keaton, being the artist and perfectionist he was, knew that if the audience couldn’t see the gags were really happening, they would fall flat. The man who helped him achieve this goal was Elgin Lessley, whom Keaton had met when Lessley was shooting Fatty Arbuckle’s comedies several years before. Like Chaplin, Keaton, when he became a star, assembled a production unit to do his comedies; it was composed of some of the top comedy writers, supporting players, and technicians in the business, united by one bond: their dedication to make the best comedies possible. No expense was too great, no task too complex for these men.

Charlie Chaplin examines the camera in his second film, KID AUTO RACES AT VENICE (1914): cameraman Frank D. Williams is at the left, director Henry Lehrman at the right

Buster Keaton checks the focal length from lens to Schnozzola. with Jimmy Durante on the MGM lot (ca. 1932).

In 1921, the unit devised an overwhelming comedy idea which became THE PLAY HOUSE. Its focal scene showed a minstrel show onstage, with nine blackfaced performers doing a song-and-dance routine. They were all to be Buster Keaton (this was the climax of a series of shots showing absolutely everyone in the theater, from the orchestra to the audience, to be Buster—literally scores of Keatons). Keaton told Rudi Blesh, years later, “Actually, it was hardest for Elgin Lessley at the camera. He had to roll the film back eight times, then run it through again. He had to hand-crank at exactly the same speed both ways, each time. Try it sometime. If he were off the slightest fraction, no matter how carefully I timed my movements, the composite action could not have synchronized. But Elgin was outstanding among all the studios. He was a human metronome.”

Such an endeavor was part of the excitement of making films in the silent era, especially for a man like Keaton. The effort was tremendous, but imagine the satisfaction these men enjoyed when viewing their finished product; indeed, it was something to be proud of. The sheer mechanical genius of Keaton’s SHERLOCK, JR. is awesome even today, with photographic devices that have never, but never, been equalled. The film stars Keaton as a movie projectionist who, in a dream, walks into the movie screen and becomes part of the film. But before he blends in with the action on the screen, he remains a separate entity, and is confounded by the fact that although he remains stationary, the backgrounds continually change behind him. Thus, as he dives into a billowing surf at the Oceanside the scene changes and Buster lands on a piece of solid ground—the new background.

Rudi Blesh summed it up quite nicely while discussing another film in his book Keaton: “No estimate of OUR HOSPITALITY is complete without mention of Elgin Lessley’s camerawork. Its clarity and beauty, altogether exceptional then, are uncommon even by today’s standards. Shots such as the views of the locomotive silhouetted on a mountaintop against the towering summer clouds are of particular beauty. Among the many things that keep Keaton’s best silent films modem—despite lack of sound, color, and wide screen—Lessley’s photography must be included.”

If one is seeking justification for the fact that so many cameramen never received recognition, it must be found in an explanation of Hollywood moviemaking at the time. Technical advances were coming to the aid of the cameraman during the 1920s, and photography in general was improving. At the same time, the studios were becoming the giant film factories that were to reign for the next thirty years, built on a foundation of high-quality filmmaking done quickly and efficiently.

The fact of the matter is, that by the 1920s Hollywood had reached a zenith in pictorial quality. Even unimportant B pictures were well photographed, and elaborate, major films had a luster that had never before been seen on the motion picture screen—indeed, it is a quality that Hollywood never really recaptured. Look at a picture like THE BELOVED ROGUE (1927), with John Barrymore, photographed by Joseph August, with art direction by William Cameron Menzies. It is one of the most visually stunning films ever made. Then watch a two-reel comedy like Laurel and Hardy’s ANGORA LOVE (1929), photographed by George Stevens. It’s just a twenty-minute short, but it is also beautifully filmed, amazingly vivid, with a full range of contrasts—qualities that might have been lacking from many feature films just ten years earlier.

One of the main reasons Hollywood became the moviemaking capital of the world was the technical brilliance which distinguished its films. By the late 1920s, this standard had established itself, and a large number of cameramen were on hand to maintain it.

Meanwhile, something was happening in Europe. In Germany, in particular, a handful of men were creating films that were not only popular and critical successes, but major contributions to the ranks of film classics. The names of these films—THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE GOLEM, METROPOLIS, THE LAST LAUGH, VARIETY-remain on the lips of film students today as prime examples of artistry within the cinema medium. And naturally, one of the major contributors to this German Golden Age was the cameraman.

In fact, it was virtually one cameraman, Karl Freund, who made his mark on the German cinema at this time by photographing most of these milestone films. For Freund, as for so many others, it was a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Born in 1890, he was working at odd jobs when, at the age of fifteen, he heard of a job opening for an assistant projectionist. He applied for the job, worked up to become a head projectionist, and before long was intrigued enough with the workings of the motion picture to talk his way into being hired as a cameraman.

The demand was great for a young man of his skill and enthusiasm, and Freund was kept busy from that time on. By 1920, he had worked with virtually all of the pioneers of German film—most of whom were still feeling their way; such men as Ernst Lubitsch, Emil Jannings, Robert Wiene, F. W. Murnau, Conrad Veidt, Paul Wegener, Carl Mayer, Erich Pommer, and Fritz Lang. With Wegener, he photographed his first classic film, THE GOLEM (1920), in collaboration with Guido Seeber. The tale of a statue which comes to life in a Jewish ghetto of Prague is an impressive work, involving some striking and imaginative trick photography when the figure is first conjured into existence in a mystical ceremony.

Gustav Fröhlich, Fritz Lang (director). and Karl Freund filming METROPOLIS (1926).

Through the early 1920s, Freund photographed Germany’s most important films, working with its greatest filmmakers. In 1924 he collaborated with the great director F. W. Murnau on what is widely c

onsidered to be one of the greatest films ever made: THE LAST LAUGH. A simple but moving story, told completely in cinematic terms (there are no subtitles), THE LAST LAUGH stars Emil Jannings as an aged but magnificently proud doorman at one of the city’s finest hotels. His spotless uniform is his symbol of respect and authority, and he wears it as a suit of armor. A young, callous manager at the hotel decides to “retire” Jannings and, as a kind gesture, gives him a token job as a washroom attendant. To Jannings it is as if his very life has been taken away. He no longer stands proud and erect but, instead, shuffles along and hides his face in shame. His mind numbed, he cannot even perform his simple washroom duties efficiently. As he changes, so does the attitude of his friends and neighbors, who scorn and laugh at the man they so recently admired.

Mood and atmosphere are everything in THE LAST LAUGH, and the camerawork is largely responsible for their creation. The lighting and photography of the washroom, as well as its physical location in the hotel, make it seem more like a dungeon. The streets outside, once bright and gay for the busy doorman, are now drab and haunting. In one famous scene where Jannings, still a doorman, drinks too much at a party, Freund strapped the camera to his waist, in order to get some shots from the intoxicated Jannings’ point of view.

The Art of the Cinematographer

The Art of the Cinematographer